Southern Peat Bogs, Old Men and A New Farm Ethic

Sitting in a rocking chair, a tiny plate of deviled eggs in his football player lap, I guessed he was about 75. He was almost a stranger yet immediately familiar. He had my father’s brogue, my uncle’s nose, and this family’s skills of storytelling, “Did you know Daddy used to run a peat company down near Edisto?”

Sitting in a rocking chair, a tiny plate of deviled eggs in his football player lap, I guessed he was about 75. He was almost a stranger yet immediately familiar. He had my father’s brogue, my uncle’s nose, and this family’s skills of storytelling, “Did you know Daddy used to run a peat company down near Edisto?”

Bagged sphagnum peat, fluffy, clean, and easy to work with, comes from up north. Go into any big-box or garden store, and you’ll find stacks of microwave sized, soft blocks marked “Canadian Peat $9.99”

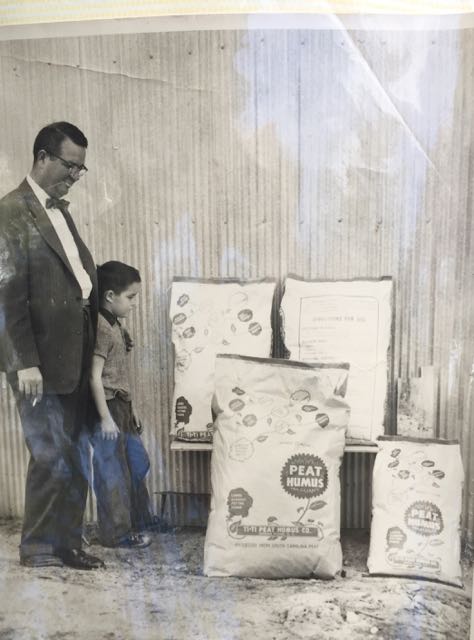

The dykes and lakes seem like a natural part of the marsh at first glance. Beautiful in a way, but this artificial environment prevents any chance of ecosystem recovery.

Back then it was really isolated. No phone, a generator for power, Daddy’s little cabin had a flush toilet, but we used a hose out back for a shower.

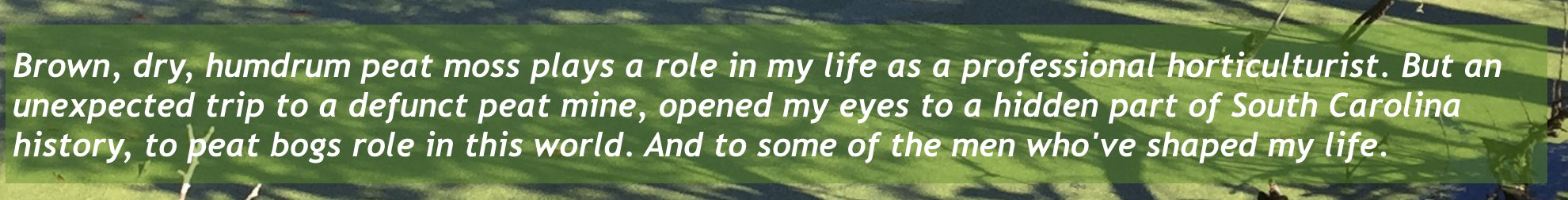

A husband, a son, a father, caretaker to an extended family, star of the local dance club, and a former captain of the football team, Bill’s daddy George Bryan was an engaged man.

George Bryan survived the first wave of Normandy, returned home to a struggling family farm then built and operated one of South Carolina’s longest-running peat mines.

George Bryan envisioned and built the system and facilities for removing peat from the wetlands, drying sifting and shipping via truck and rail.

“Noooo. He needed a job,” says Bill. “His farming forever floundered. He opened a cutting-edge welding and machine shop. You know ARC welding was new; he learned it in the war then bought surplus WWII equipment. He pioneered ARC welding in the state. But all those old farmers around didn’t have any need for an ARC welder. That business floundered, too. He needed a job. He wanted to stay near home and family and he had the war honed engineering skills to define and build the peat mining operation.”

‘How’d he get this job? Way out here?”

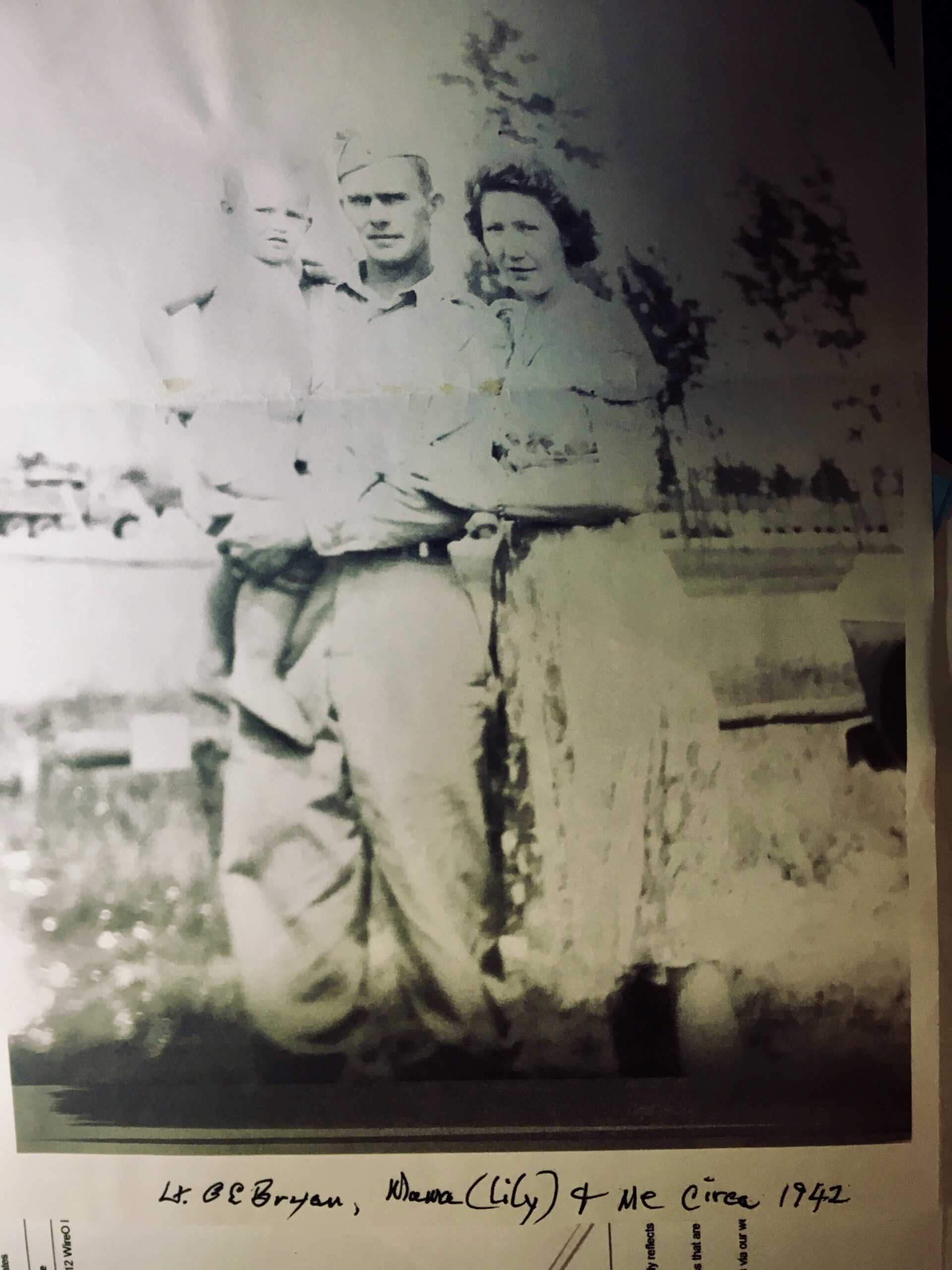

Even as his business failed, George Bryan was kept occupied as chair of the local school board, charged with building a new high school. He hired a renowned Charleston architecture firm to design it. The firm was headed by C.T. Cummings, George’s old college friend. They rekindled their friendship and planned a weekend on C.T.’s hunting land. Urbane gentlemen of the time enjoyed the luxury of having land in the country. C.T. had five square miles of brackish marsh and coastal swamp on the Ashepoo River. C.T. knew he had peatlands and liked the idea of stimulating a new industry in the state. There were grants to be had and investors who’d love to join in. CT and George hatched a plan for mining peat to be bagged and sold under their own brand, Ti Ti Peat Humus of South Carolina.

Though peat had occasional historic use in the South, mining it was pioneering. C.T. Cummins studied peat samples and use from around the world. He became president of the US Peat Association.

From his office in Charleston, C.T. made contacts, raised capital, and marketed the peat. He brought down high profile state leaders for hunting weekends: people like Robert Poole, the Clemson President man who established Death Valley football stadium.

George, who needed a job, moved to the isolated cabin Monday through Saturday. He spent the week with a crew of local workmen and carried out the project.

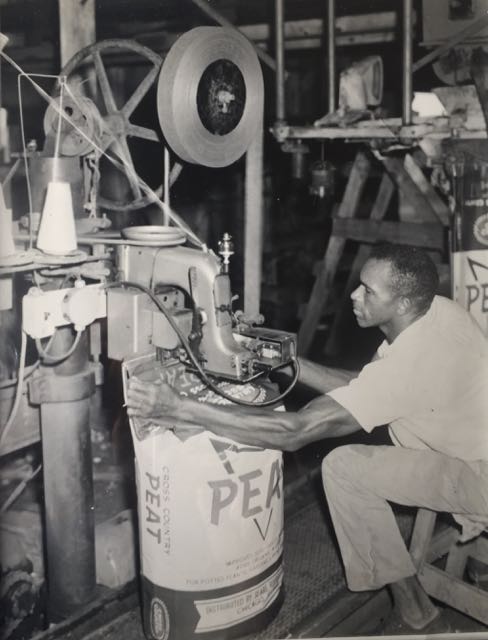

He figured out how to dig canals around ten-acre plots. These eight-foot deep canals had giant generators driving pumps moving water 24 hours a day. When the top foot of peat was dry, Franklin Days, the youngest guy on the crew, the dedicated tractor driver, tilled, windrowed, and collected peat into massive carts. He also helped with building and fabricating equipment. In the background, the tower contained giant drums to sift out roots, then conveyors for loading bulk peat.

Franklin Days fluffs and dries the top layer of peat which will then be taken to the sifting and bagging plant in the background.

Another local, Ben Hodges could fix anything. He and George amended stray parts to become a massive sifting system to sort the peat from the large debris. They even built a railway spur so they could load trains. Ti-Ti Peat went out in bags by the truck and train loads. Willy Hopkins, the most educated of the crew, delivered truckloads of peat to A&P grocery stores and to J.M. Fields and Sears department stores across the South.

George ran a tight ship. You can see it in the pictures: barns tidy; tractors, clean.

In the pictures, I also see that George must have been a well-liked leader. Probably a man of unwavering determination, who would jump right into any project, no matter how mucky, and expect his guys to jump at the same second.

I see a picture of a man named Mr. Rivers, cleaning a freshly killed duck.

Bill tells me that besides being on the crew Mr. Rivers cleaned, cooked, and took care of George Bryan’s domestic life in the cabin. Bill remembers Mr. Rivers hanging around, keeping things lively, and that he had a family with a dozen children not far away. I know the men on the crew, local fellows who lived way out in this poor, rural area, had little opportunity besides this job.

I understand that working for a man like George wasn’t always easy. And I understand that times were very, very different. But I also understand that respect and a shared mission can tightly knit together the most disparate group of guys.

But I see someone else in those pictures. More accurately, in my mind, I see my Daddy, surrounded by family and workers, tearing down a barn, rebuilding a three-story chimney, making things happen with his know-how and his expectation of unquestioned loyalty. And I see myself. Like those two men, I’d spent years working on an extended construction job in a poor, isolated, rural part of the state. But I was managing a crew of illegal Mexican men. Being sequestered, sharing a mission can bring true personal affection and camaraderie that supersedes the turmoil and tension of the world. I see that in these pictures of George and the crew of peat miners.

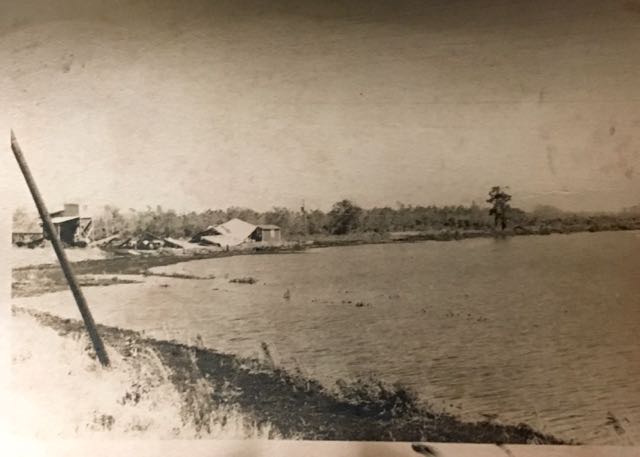

Bill and I stepped out of the truck onto a narrow sand road on top of a low dyke. On one side is an expansive rectangular lake with a dock and boat. It’s picturesque. I take a picture. On the other side of the road, scraggly trees and vines root into some concrete ruins. Thigh-thick lianas scramble on the ground trying to climb the little trees.

Bill scrubs something off his brogans onto one of the concrete walls, “This is where it was, ‘rightchere.’ This was where the tractors brought the peat from the field and dumped it. The factory was behind.”

But there’s a pond behind now, also rectangular. Thick pea-green algae covers it. “That’s where the plant was, the bagging building, the railroad spur. When they closed down, there was so much peat scattered around the plant and loading docks. They tore the buildings down and dug out everything underneath. After they dug, they flooded the mined fields. That’s why it’s a pond now.” He looks toward the blue pond across the road, “I bet there’s great fishing here.”

After tractors and men dug as much peat from the fields as they could, the fields were flooded and became the 6 feet deep ponds we see today.

The land quivers just a little as we walk. Clouds of mosquitoes, even on this December day, mask the expansive view of waist-high khaki cordgrass, faded lizard tail, and Carolina red root snaking through swaths of apple green. It looks like any marsh you see as you ride out to Isle of Palms or Botany Bay beach. But looking closer I see the soil is different, not black pluff mud. We’re standing on 1,000 acres of South Carolina peat bog. “When the train came through, the whole earth trembled. Daddy put airplane tires on the wagons, otherwise, they’d bog down out there,” Bill tells me.

I squat, rubbing my hands in the dry black powder. It feels like graphite, coating my hands. I think one of those things that I believe in my heart but don’t ever say out loud, this stuff is good for me, for healing cuts and sores and for grounding my soul. Looking down at me, Bill says, “You like dirt, too, don’t you? We all do.”

“Where was George in the War?” I ask. He answers:

“First wave of Normandy. Injured, then sent back, acted as coordinator, almost mayor, rebuilding little French towns. He was there for the fall of Paris and was scheduled to go to the Invasion of Japan. I’ll never forget the day he came home. If you could have seen the variety of people who came to see him, family, of course, farmhands, other soldiers, football team, you’d understand the kind of man he was.”

I’m getting the picture. An affable, multi-tasker, a caring manager, an exceptional delegator. Confident enough to build a new world. Grounded enough to do it on his old farm. A storyteller. An attentive father. A man at the center of family, friends, and workers. A man who expects everyone to operate as he directs. An iron fist in a gloved hand. What’s not said, but understood, was that George Bryan was loving but rigid. I understand this man, whom I’ve never met because George Bryan, Bill’s Daddy who raised my Daddy, passed all that on. Maybe some of it passed right on to me.

In the 1500s Europeans came to harvest the natural wonders of this coast. Live oak forests were cleared to be sold for ship framing, sassafras uprooted for medicine. Later, but in a similar way, agricultural crops harvested the soil. The roots of indigo, cotton, and rice tilled fertile soil until all the nutrients were simply gone. Plenty of farmers left land to erode away, just moved on.

Mining peat was just the next hope for turning the natural world into cash.

Some of those were men just in it for the money. But I know how George Bryan ran his farm. And I’ve seen C.T.’s well cared for acres of peat and marsh. They had a conservation ethic. Somehow they reconciled taking from, using, and managing the land with that ethic. It was theirs to steward, and stewardship meant to them using and repairing the best they could.

When George and crew had finished with a field, all that remained was a massive hole. And a massive pile of big stuff that got screened out; roots, tree trunks, maybe bones or whatever have been stored in that bog for the past millennium. The debris burned. The hole was filled with water. Today, those fields look like the giant rectangular lakes in the marsh. It only takes a few years for grasses and palmettos to grow around the banks, to soften the once raw pit. Today, the lakes are even inviting, picturesque, but the pattern of mining is clear in the shape of the lakes.

“Yep, great for guys who like to fish,” says, Dr. Mark Rains:

“What you see when you walk through there, those huge rectangular lakes, the grasses around the sides, the fish and the amazing array of birds, let’s be clear, that is not peatland recovery. But it’s lovely. And the guys love it for fishing and hunting. It’s what scientists call a novel environment. But it is NOT ecological restoration. We’ll never get those peat bogs, their plant life or animal life back in less than 5,000 years. There’s just no way to speed up the process no matter what people say. And, once you fill them with water, you’ll never get peat again — the water inhibits the growth of reed and grass which would slowly decay to make the peat.”

That old conservation ethic didn’t recognize any intrinsic value. But I know we’ll never recover the peat bog. We’ll never know what plants or animals were lost. Living things we should protect because it’s the right thing to do. Living things that might have been useful to us, too; medicines, foods, or chemicals of the future. We’ll never recover the dead thing either— nor the lessons those ancestors might offer.

We’ll never recover the carbon that was stored down there. Like forest trees store carbon, peat does too, only better and longer. While trees in natural cycles of decay release their stored carbon, peat bogs don’t decay, they don’t release their carbon. Though they occupied 3% of the world’s landmass, they store as much carbon as all plants in the world combined.

For a very few uses, peat remains critical. Peat filters sewage water of coliform fecal bacteria and is sometimes used in medical filters. Peat is so effective at removing diseases that you can pour dirty pond water over a cup of peat then drink the water. The same peat that holds bones, branches, and brain tissue for thousands of years also cleanses for us.

This trip has cleared up some things for me. Professionally, it’s time we stop using peat for gardening. There are better options. No petunia is worth the destruction of layered history nor the disruption of an ecosystem nor the release of stored carbon that will impact our future.

Bill takes me back to the past with one last story of how this mining endeavor unraveled for C.T and his Daddy. “I worked the summer of 59’ on the peat mine with his Daddy. Lived in the little cabin all week, showering under a hose. On weekends, we went back to Gravel Hill for farm work, meals and family. We went to Clemson together to lay out a course of study and to make a plan to go into farming business together, to save the farm.”

That fall, 1959, Bill Bryan left his Dad digging peat and went back to Clemson. What should have been a quiet weekend in Clemson, with the Tigers away at NC State, became a drama for the Southeast. Hurricane Gracie, the third-largest storm ever to hit the coast of South Carolina was bearing down. George Bryan decided to ride it out with no lines of communication. A day after the storm cleared, Bill drove down to find his dad’s pick up abandoned on a high point of the dirt road, a forest of downed trees beyond. He hiked in the last few miles to find scraps of buildings and flooded equipment. And found Willie, wandering, picking up scraps, who said he thought George might have hitchhiked north toward Charleston.

Hurricane Gracie, one of the three largest storms to ever hit South Carolina, 1959, destroyed the peat mining facility.

Indeed George had found his way to C.T.’s Charleston home. They planned reconstruction. C.T. immediately started fundraising again. Within a year, George and crew rebuilt, and the entire peat operation was running at full throttle. The whole crew was working, delivering peat.

For almost a year, they drained marshlands and dried peat. But that presents a danger, too. Dry peat makes a fine, dry, dense dust that burns easily. In fact, lightning used to spark fires that burned our coastal forests and peatlands frequently. As recently as 2008, a North Carolina peatland fire burned 41,000 acres and closed I-95. A 2015 peat fire in Indonesia may have indirectly killed up to 100,000 people through the toxic haze. It caused $16.1 billion in economic damage and released all that stored carbon.

In the summer of 1961 with peat operation running smoothly, George closed it all down as normal at lunch on Saturday and went home to his family. He was sitting down for supper when the phone rang at 6 p.m. The entire mill had burned to the ground.

Once more, George and C.T. built it back. But C.T. Cummins died unexpectedly in 1962.

George went home to the farm. Again. Bill, newly graduated from Clemson went into business with him. But like many father/son businesses, that didn’t work.

In the truck headed back to the mainland, Bill told me a lot about the old days on our family’s decaying farm. About our fathers. He speaks frankly, no romanticized memories of the glory days. There was plenty of dirt and plenty of hurt. Bill and I both had long periods of our lives when we didn’t speak to our fathers. He recalls his Daddy saying, “You better get your life straight boy, or you’ll lose any claim to this farm.”

I’d been told about the same thing once by my Daddy.

At the end of our road trip, sitting in Bobop’s gas station, we ordered fried chicken. I didn’t say it, but it made me feel close to him when I realized we’d both ordered the 2 piece dark meat only. We were quiet. I wondered if he was thinking about the same stuff I was: Daddy issues. I was thinking that we both had rigid fathers who shunned us for parts of our lives. Bill broke the silence, “I worked with tractors and farmers my whole life. You work with dirt and plants. We both got a love of the land from them. You and me.”

Our father’s influence tendriled right down in lots of ways. It made me particularly attached to place, directing my profession as a botanical garden manager, all the while balancing a tenuous relationship with Daddy. Just before he died, we sort of reconciled. I’ve been able to save his farm, to honor its past but turn it into a modern, profitable enterprise. Silly. But he’d be proud. Growing lilies may be just another way to mine the soil, to turn muscle and engineering and dirt and southern sun into plants and income. But we run the farm organically, no-till, with a new ethic.

Our clients and visitors all get a thorough explanation of why we do what we do. What we mean when we say a new farm ethic. In this case, visitors, peers, and clients will get a thorough explanation of why and how farming and gardening should and can operate without peat.

Maybe in one of this Carolina peat bog there’s some guy who followed a similar path to Bill and me. Left his clan, made his own life and family, reconciled it all, found a better way, and ended up layered in a healthy peat bog. He ought to be able to stay there.

________________________________________________________________________

Meet Bill Bryan as he explains how his Dad designed the peat mining operations

* The last peat mine in South Carolina ceased operation in 1995. Peat is still mined in 13 states. As recently as 2013, the United States Geological Survey classified peat, which grows about 1/16 of an inch a year, as a renewable resource.

*Thanks to my husband who encouraged this trip, who drove, who kept the conversations going, and edited this story.

*Thanks to CT Cummins sons, Teddy & Tim for allowing me to photograph their land and photos.

Wonderful story – thanks for sharing!

Thanks you David.

Extremely interesting to me. I have had the privilege to know both Tim and Ted for a number of years. Have hunted Deer hogs ducks alligators quail and the occasion sl turkey on the lands spoken of in the story. Fish the ponds and Walked out of the woods on the trunk banks as the sun settled across the Ashapoo. Truly a magical place with many more stories that could be told ghost trains as well getting lost in s new moon going across a bog wave on an atv on the way to a duck pot hole. Tree stand hunting the day before a major hurricane. Water moccasins alligators strange beasts who tore up a deer. Ah many more!

I’d sure like to hear the ghost train story!

Thoroughly enjoyed this story, Jenks.

Thanks Sam — more like this to come.

1/8/21 This is my favorite thing that I’ve read in 2021. I read a lot. The mix of science, family and place in this piece really spoke to me.

Wow! Thank you. I’m having such a tough time reading. Have a book coming soon I hope will prove a total escape.

Really enjoyed the story. Learning about peat bogs in SC is very interesting when it is part of your family history, Jenks. You have a way of bringing people to life in paper. Thank you.

Thank you Jenks…. I felt as though I was there with you and Bill as I read your words. Just wonderful!!

How interesting . I never knew about peat bogs in SC. You wrote it as a story, so not only did I learn something, I enjoyed it. With a strong family background in farming, I relived how difficult it was to find a way to survive. Wonderful writing, Jenks. you’ve brought back beautiful memories of growing up on a farm.

What a precious story! I did not know there was ever any peat in SC. Thanks so much for sharing SC stories intertwined with your own story.

Thanks Janice — this was all new to me too!