Carolina Vanilla Leaf

Years ago, my mentor, Bennett Baxley told me of his move to Bluffton, South Carolina. In the 50s, this tiny coastal village on the salty marshes of the May River struggled. A few wealthy folks kept quiet summer houses. Like poor people everywhere, folks looked to the wild for sustenance and income. With gunny sacks and buckets, they picked the leaves of an ankle-high weed. Bennet told me they’d haul it back to town, lay out these leaves to dry, then make them into tiny bales. During drying, the leaves got fragrant. The entire town Bennett recalled, wistfully, smelled of vanilla. Carolina Vanilla Leaf, also called Deer Tongue, bales went to cigar manufacturers in Virginia.

Known as the Deer Tongue Warehouse, on May River Road in Bluffton, the structure is now a dining/entertainment center.

This may have been “mom & pop” work, but they collected and sold tons of the stuff. Tens of thousands of tons a year came from communities like Bluffton. The story, the idea of a town that smells of vanilla, sparked my imagination, my fascination with plants, and my resourcefulness, with informal industries.

Though I’ve asked around a bit, I’ve never found anyone who remembers harvesting Carolina vanilla leaf. But it’s a great plant that still has a hold on me. We’re offering it right now, not to smoke, but to grow. Its elegant little leaves look sort of like a tiny hosta. But it thrives in terrible soil. Grow it in a pot for a conversation piece — or an incense source. Masses of purple flowers wave knee-high in August. Grow it in the ground under part shade with tiny groundcovers.

It seems the plant and the stories about it are equally hard to come by. We have a limited supply, ready to be planted right now, in the middle of summer by fall, you could harvest your own Carolina Vanilla. — Jenks

Mathew Morris did lots of web browsing to come up with the following fascinating article and links. We’ve tried to add links and acknowledge the libraries and journalists who’ve saved this information.

Vanilla Leaf, also known as Deer Tongue

Carphephorus odoratissima

As with many plants in our nursery, if you take a deep dive into the history of a plant, you are likely to find a fascinating story. Vanilla leaf is such a plant, having been inscribed into the culture of the United States right along with our tobacco heritage. Since I grew up on a tobacco farm, this was an exciting find for me. What is now a cute ornamental plant can still be found growing wild, ensconced in the same spirit of pinelands and pocosins where the Native Americans found and used it.

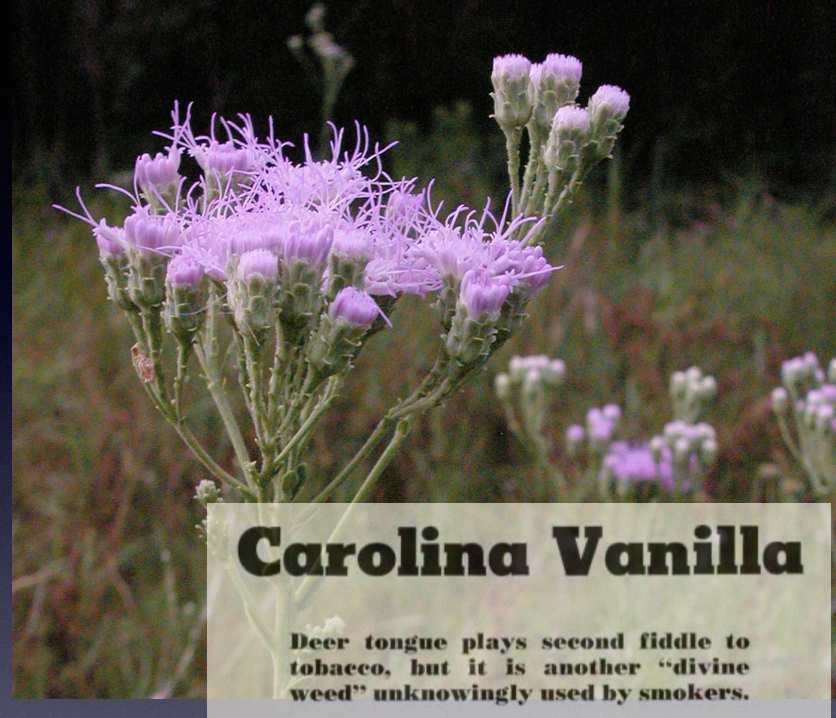

Vanilla Leaf aka Deer Tongue. Photo by USC Professor Emeritus and generally amazing man, Dr. John Nelson.

Take a look at this flower. Isn’t it precious as well as precocious, with its tight central habit and untamed whiskers? Flowering in the fall, it adds a pinkish-purple splash of spring color to a season known for its warm shades of yellow, orange, and red. The foliage is a semi-compact, low-growing rosette, that makes for a good blend between ground cover and taller more structural plants. It’s primarily found in pinelands, and pocosins in the wild in usually moist conditions. Vanilla leaf can handle occasional inundations of rain but prefers to be not too wet or dry. It enjoys full sun to part shade, like the natural filtered light of pine forests. Found to be extremely fire-resistant, vanilla leaf flourishes where controlled burns, wildfires, and other disturbances happen periodically, always bouncing back in a sign of renewal. Over time, it will add pups to the tightly-packed rosette, spreading while maintaining its beautiful form. It can thrive in sandy to loamy soils and makes a great plant to reestablish a disturbed area, such as a brand new garden space.

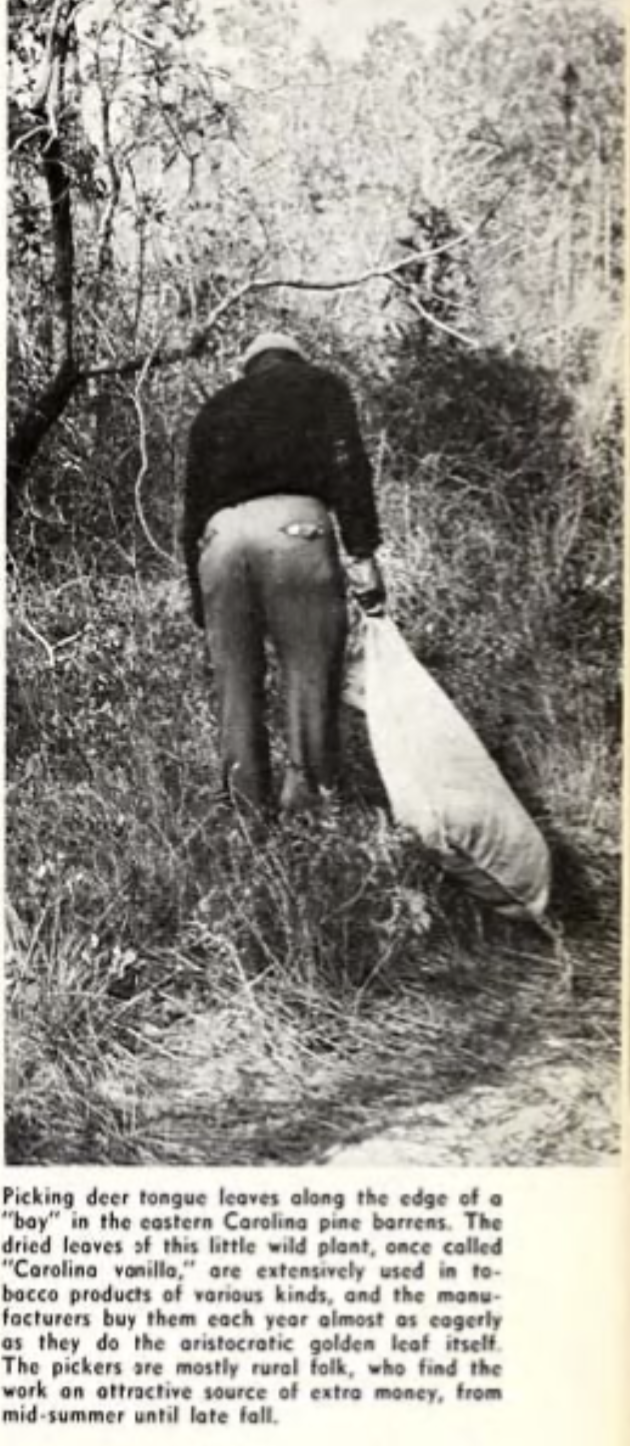

The primary use for vanilla leaf outside of ornamental planting has been as a flavoring and fixative in tobacco, cosmetics, and other personal care items. This is due to high levels of the chemical coumarin in the leaves, which has an enticing vanilla scent, which you can smell, especially once it’s dried. The Native Americans used it to blend with their tobacco, and the knowledge was passed on to settlers who continued the practice. It’s even continued up to the modern-day with certain specialty retailers. The Carolinas were the largest producers of dry vanilla leaf until 1965 when the annual production ran between three and four million pounds. It was harvested from the wilds, as commercial cultivation proved problematic. Every year people from all over the Carolinas where vanilla leaf can be found would work in their spare time going through the woods searching for the fragrance of sweet vanilla emanating from the forest floor. With their sacks, they gathered the profitable crop, which sometimes grew in the woods alongside the fields of tobacco with which it would ultimately be blended. Once harvested, anytime between June and the first frost of the year with more mature leaves being desirable, the plants were laid on blankets in the sun to dry. After drying, they were sold, primarily to tobacco manufacturers in Brunswick, GA, Bluffton, SC, and Richmond, VA, which were among the largest tobacco-producing communities. The tobacco industry didn’t exactly advertise that they were adding vanilla leaf to their tobacco, but it eventually became fairly commonly known.

On early homesteads, vanilla leaf might have been found hanging in wardrobes or placed in chests to impart its soothing vanilla perfume to clothes. The tannin compounds found in the plant may also have a similar effect as cedar in preventing insects such as moths from making a meal out of the clothing so precious to early settlers. Besides a flavoring or scenting agent, the tannins found in vanilla leaf are known to “fix,” or prevent the degradation of, the other scents and flavors of products with which it is combined. So it has been used in cosmetic products, such as soap, to not only impart its lovely aroma but to keep other scents from essential oils from deteriorating. It was even used in artificial vanilla extract production until 1952 when it was banned for internal use in the United States. This ban was primarily instituted due to the apparent effects of coumarin thinning the blood and possibly causing liver damage. Despite this, around the world vanilla leaf has been used as a treatment for malaria. Native Americans and settlers would use vanilla leaf as a sort of cure-all tonic, as it has stimulating and sweat-inducing properties, at least in anecdotal reports. Somehow, tobacco products escaped this fate, and blends of tobacco with vanilla leaf can still be bought today.

As a perennial herb coming back as it does even in highly disturbed habitats such as fields and burned areas, vanilla leaf serves as a reminder not only of culture and history but also of the lifeforce found in humble plants all around us. It’s a wonderful addition to the garden, whether in flower or not, as the foliage is lovely. Offering scents and flowers normally associated with spring, it is a delight to the senses when a lot of other plants are beginning to wane.

Great story. I’ve never heard of this and I’ve lived in SC all my life.

Hi!

Great story as I have never heard of this Deer Tongue/Vanilla Leaf and I agree up in Aiken, SC from 1960 through 1981.

Love Jenks Farmer and Staff for all they do and represent in this state and world.

Keep it up…👍

Wonderful and educational story!

Thank you 😊

Do deer like to eat it (I know they will eat anything once, except crinums or iris), or is it

‘deer resistant’?

I have no idea!

Binomial nomenclature of Carolina Vanilla Leaf plant?

Carphephorus odoratissimus

Love the story, we love growing unusual plants. Now to see where we can find this plant, thanks for sharing this story. I wonder if it would be good for honey bees.

This is great! Well done Jenks. I love learning new things about plants. I see this plant often when hiking the forest here in north Florida.

have you ever cultivated it? i’m hoping it’s not fire dependent